What is All Saints' Day?

Halloween or All Hallows' Eve: Sanctity versus spectacle

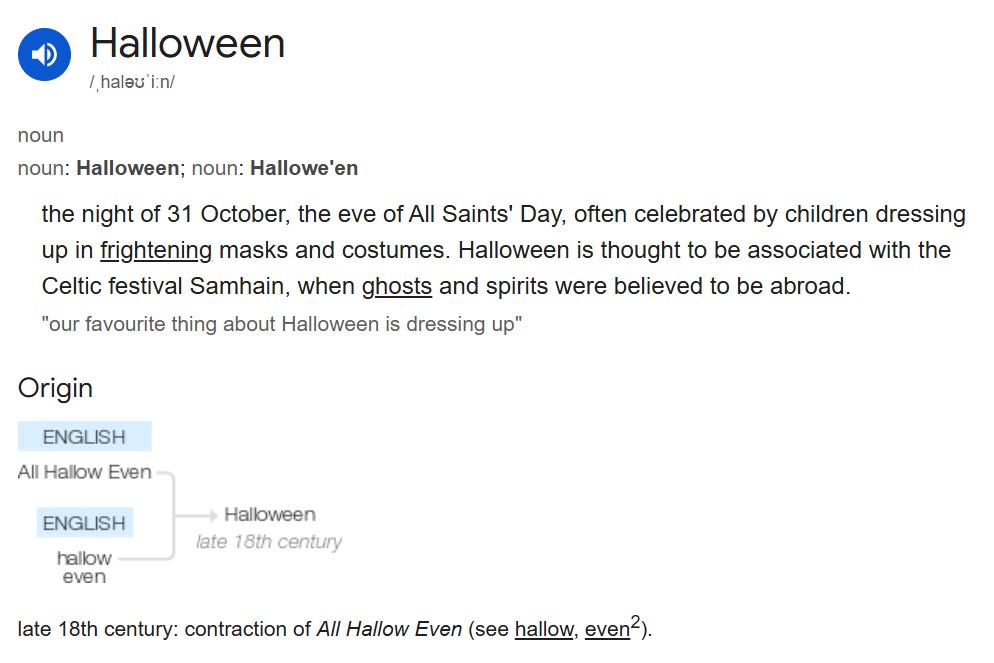

All Saints’ Day or All Hallows’ Day is a Catholic feast day or solemnity, celebrated annually on November 1st. It is preceded by All Hallows’ Eve, or Halloween; like Christmas Eve it is a day of preparation for the celebration of the feast on the subsequent day.

The feast can be traced back to early Christian practices of commemorating martyrs, particularly in Rome. It became a general feast for all saints by the 9th century, and Pope Gregory IV officially declared November 1st as its universal date of celebration in 837 AD.

It is thought that Pope Gregory IV chose this date as a means to compete with the ancient Celtic pagan holiday Samhain (pronounced Sow-in), which marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the “dark half” of the year. The Gaels who observed Samhain believed that on this day, the boundary between this world and the ‘Otherworld’ blurred, making contact with 'spirits' or ‘fairies’ more likely. Offerings of food and drink were made to these deities to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. The souls of dead relatives were also thought to revisit homes seeking hospitality, and a place was set at the table for them during a meal. Guising was a key part of the festival, with children dressing in costume and going from door-to-door reciting poems in exchange for food: where modern “trick-or-treating” on Halloween on October 31st originated. In folklore, jack-o’-lanterns, also called will-o'-the-wisps, were attributed as ghosts, fairies, or elemental spirits meant to reveal (or conceal) a path or direction. The phenomenon is said to guide or mislead travellers by resembling a flickering lantern.

It is believed that Samhain and the Christian holidays of All Hallows’ Eve and All Saints’ Day (All Hallows’ Day) influenced each other and the modern Halloween. Religious syncretism is an interesting phenomenon. It calls to mind the age-old battle between good and evil that runs through Christian theology: cavemen gather to discuss plans for start of cold season, pagans give it a ritual form centuries later, centuries later still the Church takes a pagan holiday and sanctifies it, and then the pagans put it back a little louder (commercialisation) but also a little quieter (secularisation). Modern capitalism, the servant of Mammon, likes to convert every festive season into an opportunity to buy new stuff. All of a sudden, we have strange symbols to associate with these events. Jack O’lanterns, Halloween “decorations”, candy, costumes, the lot.

But All Saints’ Day, the day after Halloween, hasn’t been appropriated by the modern age in the same way. Halloween has been fully absorbed into the capitalist calendar, an event advertised months in advance, a ritual of consumption more than remembrance. All Saints’ Day, by contrast, remains largely unmarketed. There are no All Saints’ sales, no aisles of plastic halos.

In many European countries, All Saints' Day is a public holiday. Traditionally, people use the day off as an opportunity to commemorate passed loved ones, visiting their graves and spending time with family.

In the Catholic country of Poland, cemeteries are deep-cleaned, with graves even washed in preparation for All Saints’ Day to accommodate the visiting crowds. Poles take millions of candles into the cemeteries where the graves of family, friends, or national heroes are. Candles are specially designed with paraffin wax to burn for hours, lasting all night. Almost every grave has a cross standing or carved in stone. It is believed that praying and putting candles on these graves can help the souls of the deceased.

In Portugal, children go door-to-door asking for special bread, a tradition akin to the historical practice of "souling" for soul cakes in exchange for prayers. In France, people decorate graves with flowers, notably the chrysanthemum, a post-WW1 tradition for the graves of soldiers. 22 million of the 23 million chrysanthemums sold in France every year are sold on All Saints’ Day.

As the name suggests, All Saints’ Day honours all the saints, those canonised by the Catholic Church (capital “S”) but also those who have lived exemplary holy lives but are not publicly recognised as saints. Saints are sought out by the Church for public canonisation as a means to contribute to the health of the religion on Earth, but this definitely does not change the status of the individual in Heaven; it is merely a reflection. The tradition of saint-making is itself a deeply evangelical one, it upholds the example of holy lives for Christians to follow, and also brings people to the faith. On Earth we can never know the full scope of saints in Heaven, of course, there are far, far more than the canonised 10,000. And the true contents of the heart is something only revealed to and perfected by God. So, what exactly is a saint?

The definition of a saint is anyone who is alive with God in Heaven. To become a Catholic Saint canonised by the Church, one must have lived a life of heroic virtue, and after death, have at least one or two miracles attributed to their intercession. At least one miracle is required for beatification (being declared "Blessed"), and a second, separate miracle is typically required for canonisation (being declared a "Saint"). The ability of the deceased to perform a miracle on Earth is only possible if they are alive in Christ in Heaven, as they are in union with God, who, while incarnate as Jesus, performed countless miracles. In the 20th century, 99% of these miracles attributed to the saints have been medical, most (un)commonly a miraculous healing. To prove a miraculous healing, the Vatican opens an extremely rigorous procedure and convenes a committee of doctors to evaluate a patient’s medical records and testify that there wasn’t a scientific explanation for a cure. The subject would have had to pray exclusively to the saint and, in the proceedings, swear by this fact, in order for that miracle to be assuredly attributed to the saint.

Christians often talk about being “alive in Christ” or part of the “Christ-body.” St Paul wrote of this in his letters to the Romans and to the Corinthians: “In Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others.” (Romans 12:4–5). “Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it.” (1 Corinthians 12:12–27)

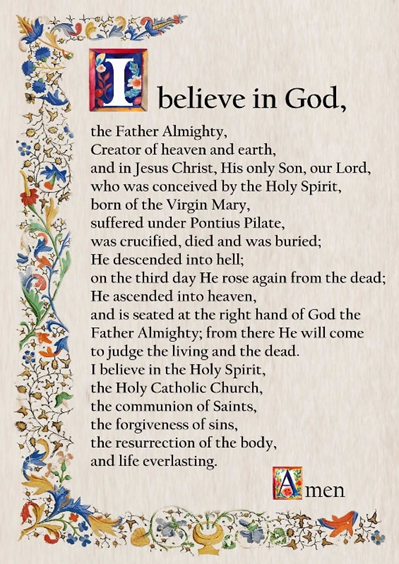

When we say the Apostles Creed, we say we believe in the “communion of Saints.” All Saints’ Day celebrates exactly this. The Church teaches that the Communion of Saints is a collective, spiritual union of everyone in the faith: those living on Earth, those being purified in Purgatory, and those already in Heaven. It’s a recognition of the triumph of God’s grace in individuals, but also as a collective. As brothers and sisters in Christ, we are a family. It reminds us that we have a family in the innumerable Christians before our time. After sharing the story of my faith journey with a lady at a non-denominational church, she told me, “All of Heaven is cheering you on”. This really stuck with me and helped me contemplate what community, in the spiritual sense, is truly like.

The Church “one flesh” with Christ

In 1 Corinthians 12:12–27, Paul compares the Church to a living organism, with Christ as the head, and the believers comprising the many members of the body (hand, foot, eye, etc.) with unique gifts and roles, all essential to the whole.“Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ.” (v.12)

At St. Joan of Arc’s trial in 1431, she was interrogated about her loyalty to the Church. One of her most famous statements, recorded in the trial transcripts, is: “As to the Church, I love it and would wish to support it with all my power, for our Lord and the Church are one and the same thing.”

The notion of the Church as one with Christ is also emulated in the metaphor of the Church as the bride and Jesus as the Bridegroom.

Paul writes in his Epistle to the Ephesians 5:25–32,

“Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her, that he might sanctify her... that she might be holy and without blemish. For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh. This is a great mystery, and I am applying it to Christ and the Church.”

Paul directly applies Genesis 2:24, “the two shall become one flesh,” to the union between Christ and His Church.

United Suffering

The suffering of the Church and Christ’s Passion are inextricably linked.

“If the world hates you, know that it has hated me first.” (John 15:18)

When Saul persecutes the early Christians, Jesus identifies Himself directly with them: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4)

As Christians, we are individually called to “carry our cross”. As followers of Christ, we “walk with” Him, embracing the daily rejection of the deception of our hearts and desires.

As her Lord once descended to Hell and triumphed, so “the gates of Hell shall not prevail against her” (Matthew 16:18), the Church lives the very mystery of Christ: crucified in weakness yet raised in the power of God.

Unified in the Eucharist

The idea of also being “alive in Christ” or “in the Body of Christ” extends also to the Sacrament of the Eucharist, which is also referred to as “The Sacrament of Life”.

“Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise them up at the last day.” (John 6:54)

When we participate in Adoration, we are in the True presence of Christ. When we consume the Eucharist at Mass, we are all collectively sharing in the life of Christ.

Another name for the Eucharist is Communion.

“The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one loaf, we who are many are one body, for we all share the one loaf.” By eating from the same bread and drinking from the same cup, believers express and deepen their unity in Christ and with one another.

As Catholics, we know that taking the Eucharist is not simply physically eating the body of Christ, but spiritual consumption; it’s my soul that eats.

Protestants or non-denominational Christians will sometimes stress relationship over religion. While relationship with God is indeed the most vital aspect of the faith, participation in the Church through the Sacraments is an invitation to connect with Jesus Christ through divine intervention in a way that unites the physical and spiritual; a divine mystery that deepens our relationship beyond what the merely human or emotional can achieve. The community arising from organised religion isn’t just the parish present at Mass every Sunday, it’s the idea that we are a spiritual family unified in the Communion of Saints.

Since the time of Jesus, the collective participation of believers in the Sacraments has been an essential part of Christian faith and life. In addition to the Sacraments, Christians are united through the celebration of the Church’s liturgical feasts, which express our communion as the Body of Christ across time and space.

The Solemnity of All Saints, like other feasts, unites Christians in shared celebration, yet this feast is distinct in that it invites us to introspectively honour that very unity. In celebrating All Saints’ Day, we celebrate all the faithful throughout history who now share in the glory of God. Through the Church, physical community becomes spiritual Communion.

Thanks for reading! You can find the full article here: Halloween or All Hallow’s Eve: Sanctity versus Spectacle

References

- Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press, 1996. Wikipedia

- James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (various editions). Wikipedia

- John T. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. Wikipedia

- Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, Myth, Legend & Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. Wikipedia

- Ann Dooley & Harry Roe (eds.), Tales of the Elders of Ireland: A new translation of Acallam na Senórach. Oxford University Press, 2005. Wikipedia

- McKeever, Amy. “What Does It Take to Become a Saint in the Modern Age?” National Geographic, 8 Sept. 2025.

- Hardon, John. “Miracles of Christ.” CatholicCulture.org (Catholic Dictionary). Trinity Communications.